| |

|

Endgame In Punjab: 1988-1993

K. P. S. Gill*

I

The movement for the creation of Khalistan

was one of the most virulent terrorist campaigns in the world. Launched

in the early 1980s by a group of bigots who discovered their justification

in a perversion of the Sikh religious identity, and supported by a gaggle

of political opportunists both within the country and abroad, this movement

had consumed 21,469 lives before it was comprehensively defeated in

1993.1 Thousands of others were injured

and maimed, hundreds of thousands were permanently scarred by their

experience of dislocation, the gratuitous loss of loved ones, and an

unremitting terror that they endured for more than a decade.

The campaign that eventually crushed

this menace, as dramatic as it was significant in its strategic inventiveness,

has received little systematic attention. Apart from the reportage and

commentary it attracted in the mass media during its execution, the

only sustained attention it has received has been in the form of propaganda

by the front organisations of the defeated terrorist movement, and by

apologists masquerading as human rights activists purporting to present

a "history" of the "sufferings of the Sikh people".2

Neither group has shown, or could be expected to show, even a cursory

respect for facts or evidence. Not only has this manifestly slanted

debate excelled in the invention of political fictions, it has failed

abjectly to explicate, analyse and evaluate the wealth of strategic

experience that this campaign generated.

One of the dominant myths that these

propagandists have tirelessly, and in some measure successfully, circulated

is the idea that terrorism in Punjab was defeated, not because, but

in spite of the use of armed force against the militants. No evidence

is ascribed to shore up this claim, but a variety of nebulous theories

– essentially populist and politically correct slogans – are

propounded regarding a ‘people’s victory’ or a ‘political

solution’ that brought peace to the strife-torn province.

The defeat of terrorism in Punjab, and

I have said this before3, was unambiguously

the result of the counter-terrorist measures implemented in the state

by the security forces. Moreover, the use of this coercive force was

(and is) not just a necessary expedient, but a fundamental obligation

and duty of constitutional government, and its neglect inflicts great

and avoidable suffering on the innocent and law abiding. This is not

simply an assertion of subjective belief, but a fact that is well borne

out, as I shall attempt to demonstrate, by the overwhelming weight of

evidence generated during the Punjab campaign. Specifically, I shall

seek to demonstrate that each time a ‘political solution’

was sought through a dilution of the operations carried out by the security

forces, through negotiations with terrorists and their front organisations,

and through measures referred to as "winning the hearts and minds

of the people" – usually an euphemism

for a policy of appeasement of terrorist elements – terrorism escalated,

as did the threat to the integrity of the nation, and the innocent victims

of terrorism multiplied.

Counter-terrorist and counter-insurgency

operations in Punjab also challenged established traditions of response

to situations of extreme and widespread militancy. By and large, once

political violence escalates beyond a certain limit (which may vary

from situation to situation, and according to political perceptions),

conventional wisdom conceives of the army as a refuge of last resort.

This was, and remains, the case in most campaigns within India, as it

is in most areas of major civil strife in other parts of the world.

Even those who strongly advocate the exclusive use of the civil police

to confront all internal security challenges and see a "fundamental

conflict" between internal security duties and "the professional

instincts, traditions and ethos of the military" concede that a

resort to the army is a legitimate "last line of defence"

even within "the strict limits imposed in a constitutionalist liberal

democratic system".4

Within India this advocacy of, and inevitable

resort to, the army in circumstances of widespread disorder is also

based on an implicit (even occasionally explicit, though not publicly

proclaimed) assumption: the presumed subversion of the local police

force in any situation of large-scale insurgency or civil strife. Divided

loyalties or the "unreliability" of the local police have

been used to justify the withdrawal of the government’s faith in

this force in theatres of low intensity conflict in various states of

India’s North-East, in Jammu and Kashmir, and, for several years,

in Punjab as well.

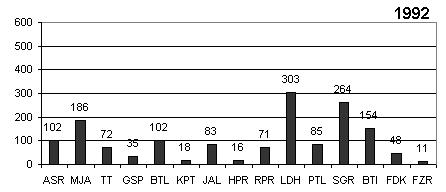

Fig.

1: Force Casualties in Punjab - 1981-96

The Punjab campaign, however, eventually

demonstrated not only that the civil police was an effective counter-terrorist

force even in the most extreme circumstances, but also that the presumption

of bad faith was completely unfounded. The role of the army and of para-military

forces was, of course, critical in the final phases of this campaign,

but it was the Punjab Police that spearheaded the anti-terrorist offensive

– and this is clearly borne out by the relative casualties these

various forces suffered [Fig. 1].

Both the devastating consequences of various "political

solutions" and of a resort to conventional military strategies

against terrorism are borne out startlingly by even a cursory review

of the pattern of conflict and response that prevailed in the initial

phases of the terrorist movement in Punjab. Counter-terrorist strategies

at this stage vacillated between the extremes of paralysis and over-reaction,

even as political responses and policies ranged from opportunism through

cynicism to panic. It was only towards the end of the Eighties that

mounting violence and a mix of exhaustion and alarm made at least some

political leaders and regimes – though certainly not all –

more amenable to a realistic appraisal of the threat and to the dictates

of reason.

It is not my intention to review this initial phase

in detail. Certain elements, however, demand elaboration, to the extent

that they define the context of the events and strategies that evolved

later.

Terrorism in Punjab has, on occasion, been projected

as a natural consequence of the unfulfilled collective aspirations of

the Sikhs, as "an idealistic movement for the creation of a state…

among the Sikhs of the Punjab".5 The

fact, however, is that the movement for Khalistan was created out of

a pattern of venal politics, of unscrupulous and bloody manipulation,

and a brazen jockeying for power that is too well documented to be repeated.

It will suffice to state here that each of the major political players

in the state and the national arena participated in the creation of

this calamity, and the Congress (I) and the Akali Dal were the most

culpable formations.6 This, indeed, was

the first stage where a pernicious pattern of political intervention

contributed, not to the resolution, but to the creation and nurturing

of terrorism.

Nor indeed, were any ‘Sikh aspirations’ involved

in the movement for Khalistan. Far from being a revolution against ‘oppression’,

this was actually a rebellion of a privileged quasi-feudal caste-based

orthodoxy that saw its privileges shrinking. It was, moreover, entirely

unconnected with any element or principle of Sikhism, and was based,

rather, on a corruption and perversion of everything that Sikhism has

historically represented. In it, "the institutions of the Sikhs,

both religious and political, …[were]… hijacked by a small

clique, a self-interested oligarchy, representing a particular ethnic

cluster, a small endogamous segment of Punjab’s social fabric;

a narrow caste group that…[sought]… to define Sikhism and

Sikh identity in terms of its own constricted vision."7

This convoluted pattern of politics, of competitive

communalism and brinkmanship in the Punjab, produced the larger than

life image of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. An image that owed its proportions

as much to the political leadership of that time as it did to the media

and, eventually and overwhelmingly, to his seizure and control of the

Golden Temple – the most hallowed shrine of the Sikhs. Whatever

the causes, it is a fact that, by 1984, Bhindranwale’s murderous

creed had captured the imagination of a significant number of Sikhs,

particularly in rural Punjab.

The years preceding 1984 are particularly inglorious

for the Punjab Police and its leadership. Their failure to act against

extremist elements was comprehensive. It was, nevertheless, understandable.

Before the 1980s, terrorism had only been experienced in India in regions

that were regarded as ‘peripheral’ to the ‘national mainstream’.

The North-East had long been troubled by bloody insurgencies, but was

generally viewed as an amorphous ‘disturbed area’ that invited

a certain pattern of armed intervention, primarily through use of military

force. Having served a quarter of a century in that region, I had seen

these campaigns at close quarters and had long regarded them as an inappropriate

model for intervention – one that reflected not only political

short-sightedness, but also a strategic failure of monumental proportions.

In Punjab, however, the shock of terrorist tactics – unfamiliar

in the extreme – produced a paralysis that was compounded enormously

by the conduct of politicians at the very highest level. To expect a

sagacious, balanced and adequate response from district police officials

against extremism that is clearly, directly, sometimes openly, encouraged

by leaders at the highest levels of governance, is to ask for the impossible.

In any event, in the absence of a clear mandate and a firm leadership,

the police, directionless and demoralised, quite simply, refused to

engage.

I was not present in Punjab at this juncture, but there

was ample evidence of this abdication of responsibility even when I

was transferred to the state in September 1984 – a full three months

after Operation Blue Star. I held joint charge as Inspector General

(IG) of the Punjab Armed Police (PAP) and IG Operations. In both capacities,

my jurisdiction comprehended counter-terrorist operations right across

the state, and I was astonished to discover that simply no records were

being maintained in connection with terrorist crimes, no investigations

were carried out, and almost invariably, no documentation existed of

any action taken. There was widespread reluctance on the part of Punjab

Police officers to involve themselves in anti-terrorist work. Many of

the interrogations had to be carried out by officers at a senior level,

as Station House Officers [SHOs] and subordinates at the police stations

were clearly unwilling to be associated with the process for fear of

identification and reprisals. As IG Operations, records relating to

terrorist crime and profiles of terrorists were essential to my work,

and it was only after this stage that a slow and painstaking process

of record-keeping and analysis was established.

Political mischief, a mounting campaign of demonstrations

and bandhs orchestrated to coincide with terrorist actions, increasing

and unpunished incidents of extremist violence, the evident impunity

with which terrorists acted, and the total uncertainty and apathy that

attended the actions of the law enforcement machinery, had, by 1984,

created an atmosphere of terror and collapse of the state that was far

in excess of anything that the situation itself warranted. Between 1981

and 1983, the terrorists had killed 101 civilians. Of these, 75 were

killed in 1983 itself [1981: 13; 1982: 13] – an event that, in

the prevailing state of hysteria, inspired one commentator to refer

to this as "The Year of the Armageddon";8

disturbing though the numbers were, this evaluation was more than excessive.

Indeed, even in the years preceding the advent of terrorism in Punjab,

the number of murders in the state were seldom below 500 in any year,

and tended to maintain a secular upward trend [1981: 555; 1982: 575;

1983: 591].9 More recently, in the three

years after terrorism was brought under control in Punjab there have

been a total of 2,081 murders unrelated to terrorism [1994: 687; 1995:

686; 1996: 708]. These numbers are not regarded as being extraordinary,

and have attracted no exceptional comment in the media, nor was there

any sense of a "breakdown" in the state.

Without doubt, the impact of terrorist killings –

as a result of their sheer brutality, irrationality and randomness –

is far greater on the public mind than that of an ordinary criminal

act. It is only natural for a poorly informed and sensation-hungry media

to devise frenzied headlines. But for the police administration to act

as if these represented an objective evaluation of the threat potential

is inexcusable.

But the police, no doubt stupefied by the sheer unfamiliarity

of the challenge, was also not permitted to act; nor did it dare to

act on its own against the manifest intent and stratagems of political

powers. The result was that, in the months preceding Operation Bluestar,

terrorist violence mounted to claim 158 civilian lives between January

and May 1984.

The sheer intensity of police paralysis at this time

has been substantially documented. Right since the Daheru incident in

1981, when an ill-prepared police party, when shot at by a group of

terrorists whom they had gone to arrest, abandoned its weapon and fled,

there had been acts of dereliction without number. Nevertheless, there

is one incident that bears repetition, as it reflects the abysmal depths

to which the spirits of the law enforcement agencies had plummeted.

A single incident epitomises their impotence. On

February 14, 1984, a group of militants attacked a police post at

some distance from the entrance of the [Golden] Temple. Six policemen,

fully armed, were ‘captured’ and dragged inside. The ‘police

response’ came twenty four hours later in the form of a senior

police officer who went to Bhindranwale in the Akal Takht and begged

him to release his men and return their weapons. Bhindranwale agreed

only to hand over the corpse of one of the policemen who had been

killed. He later relented and released the remaining five men who

were still alive. Their weapons, including three sten guns, and a

wireless set, were not returned. No one asked for them. No action

was ever taken in the case of the murdered policeman.10

I cannot imagine any police force in

the world reacting to such an outrage with such utter cravenness, in

such complete and impotent prostration.

Nevertheless, even under the prevailing

circumstances and with the victims of terrorism multiplying rapidly,

I cannot believe that what was done under Bluestar could be justified.

It is my firm conviction that with the right leadership and a clear

and unambiguous political mandate, the police morale could have been

revived [as it was, much later, and in a situation that was far worse]

to secure effective action; and that concerted police action, with suitable

para-military and army backing, would have produced better results even

at this stage. Instead, in an ill-planned, hasty, knee-jerk response,

the Army was called in: artillery battered the revered edifice of the

Golden Temple Complex, and tanks rolled across the holy parikrama.

The army, however, was not to blame for this botched operation; it was

acting on specific directions from the Prime Minister’s Office,

and had been given little choice or time to prepare.11

The damage Bluestar did was incalculable.

This was compounded by Operation Woodrose, the Army’s ‘mopping

up’ exercise all over Punjab that sought to capture Bhindranwale’s

surviving associates and to clear all Gurudwaras in the state

of extremist elements. Woodrose suffered from all the classical defects

of army intervention in civil strife – an extraneous and heavily

armed force suddenly transported into unfamiliar territory; mistrustful

(in this case, exceptionally so) of the local police and intelligence,

but with no independent sources of information; dealing with a population,

large segments of which had become hostile; and operating under a political

fiat that not only condoned, but emphasised the use of punitive force.

Operating blindly, the army arrested large numbers of people, many innocent,

others perhaps sympathetic to the militant cause, but by no means associated

with any terrorist or criminal activity. Lacking in adequate information

to distinguish effectively at the local level, the indiscriminate sweep

of Woodrose pushed many a young man across the border into the arms

of welcoming Pakistani handlers. And then, even as Woodrose drew to

an end, the evil was incalculably compounded by the pitiless massacre

of Sikhs in what were perceived to be Congress-I government-sponsored

riots of November 1984.

I regard Operation Bluestar and the

November 1984 massacres as "the two most significant victories

for the cause of ‘Khalistan’…not won by the militants,

but inflicted…. upon the nation by its own Government… These

two events, in combination, gave a new lease of life to a movement which

could easily have been contained in 1984 itself."12

After the army, it was the turn of the

‘political solution’. The Rajiv Gandhi government, having,

in its first days, remained a mute spectator to the anti-Sikh riots,

decided to force the ravaged state through a hasty and ill-timed election.

Negotiations were initiated by the central government in mid-1985. The

Akalis, led by Harchand Singh Longowal, assisted by S. S. Barnala and

Balwant Singh (of whom Longowal and Balwant Singh later fell to assasins),

showed great eagerness to reclaim their hold on events in the state.

But the Centre’s ‘strategy’ went well beyond the ‘moderates’

in the Akali Dal, and the government also initiated a dialogue with

representatives of the All India Sikh Students Federation (AISSF), at

that time a frontline terrorist grouping. I was asked, initially, to

be present at the meetings between the AISSF and the government’s

intermediaries, and subsequently, to intervene. Eventually, the AISSF

representatives expressed their willingness to join the electoral process,

but demanded a short deferment of the projected dates in order to prepare.

The Akalis who were negotiating separately with the government, however,

objected strongly, fearing that the AISSF, given this time, could sweep

the elections. The talks with the AISSF broke down on this trivial difference,

mainly because of the Centre’s inclination in favour of the Akalis.

The entire move to install the Akalis

in power was most unwise. It was based on an erroneous premise that,

just as the Marxists [Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI-M)] had

tackled Naxalism [CPI (Marxist-Lennist) terrorism] in West Bengal, the

Akalis would fight Sikh terrorism in Punjab. This was a complete misreading

of the relationship between the Akalis and the extremist. I was strongly

opposed to the elections of 1985, and repeatedly expressed my reservations,

because I was convinced that there was no real difference between the

fundamental thinking of the Akalis and the terrorists – and that

the Akalis completely lacked the desire and the will to contain terrorism.

I was equally convinced that terrorism would return with a vengeance

within six months of the Akalis forming the government – and events

soon demonstrated that even this projection was an overestimation.

The elections eventually took place

– but only after Longowal’s assassination – on August

20, 1985. Sympathy, and the lack of any serious opposition in the elections

on September 25 returned the Akali’s, now led by Barnala, with

a sweeping majority (73 out of 117 seats).

One of the first acts of the Barnala

government was the appointment of the Bains Committee which released,

en masse, over 2000 extremists at that time under detention.

The impact on terrorist violence was palpable – not only because

those who were released simply resumed their activities, but also because

others saw in this act a restoration of the immunity they had enjoyed

in the pre-Bluestar phase. 1985 had seen a total of 63 civilians and

eight policemen killed by militants. As the Bains committee began its

work, in just the first three months of 1986, 102 civilians and 10 security

men fell to the terror.

Barnala also surrendered the Golden

Temple to the terrorists once again. The shrine was restored to the

Akali controlled Shiromani Gurudwara Prabandhak Committee (SGPC) on

January 22, 1986. In less than a month, the terrorists, led by the Damdami

Taksal, were in complete control. The SGPC, in fact, had to shift the

venue of its Sarbat Khalsa (the general assembly of all Sikhs)

to Anandpur Sahib, because it was in no position to hold the event within

the Temple precincts. Once again, murderers swaggered across the parikrama;

proclaimed offenders, wanted by the police for the most heinous crimes,

planned and directed their activities from the security of the hallowed

complex; assassins installed themselves in the highest religious offices.

By the end of April, a ‘Panthic Committee’ had been

constituted to coordinate all terrorist activities, and a ‘Declaration

of Khalistan’ was issued by the Committee from the Golden Temple

(April 29, 1986). A day later, the Barnala government ordered a mock

search in the Temple with ample advance notice. It was an ill-conceived

and ill-planned raid (occasionally, if inappropriately, referred to

as ‘Black Thunder-I’) mounted by the National Security Guard

(NSG). The sum total of the impact of this Operation was the use of

stun grenades that resulted in the burning of a book shop near the gate

of the Temple, the beating up of two granthis after they had

been chased off the parikrama, and the interruption of an akhand

path due to the disturbances. Not unexpectedly, "no one of

note was caught"13 in this action.

The incident, however, was sufficient to provoke a split in the Akali

Dal, and, from that point onwards, Barnala’s existence was entirely

dependant on the Congress-I’s support. Nevertheless, after their

very brief ‘absence’ the terrorists simply returned to the

Temple and resumed control. The saga of complicity and cowardice that

abandoned the Temple and the state to the depredations of the terrorists

demands independent documentation. The simple fact, however, is that

during Barnala’s brief and feckless tenure of a little over 19

months, the lives of 783 civilians and 71 security men were sacrificed

in an ill-conceived political gambit that was predestined to failure.

The ‘political solution’ had

borne its bloody fruit.

But the harvest was to continue a great

deal longer. The violence escalated continuously as both the political

and the police leadership failed consistently to define an unambiguous

response to terrorism. Indeed, there was no concerted and consistent

bid to confront the problem squarely, no political strategy, and no

clarification of the principles of administrative, judicial and executive

response to the scourge.14 The police response,

to the extent that it was mandated by the political executive, was itself

muddled. Dictated by traditional notions of use of force in situations

of civil strife, the dominant thinking emphasised the ‘minimum

use of force’ against the unconstrained violence of the terrorists.

This thinking persisted among many police officers at the senior-most

level even after the introduction of the sophisticated Kalashnikov assault

rifle [the AK-47] into the terrorist armory after May 1987.15

With the supply of Kalashnikovs to the terrorists, Pakistan had clearly

increased the stakes of its covert war in India, and terrorism, at this

point, entered a completely new and deadlier phase. The impact was immediate

and dramatic. Explosives were yet to play a major part in the terrorist

strategy in the state. Though crude bombs extracted a steady toll of

innocent lives, it was only after 1990 that sophisticated explosives

became an essential component of the terrorist combat gear supplied

by Pakistan. The scale of killing, consequently, was directly connected

with the gun-power available to the terrorists – and did not recede

to the pre-1987 level until the terrorists were finally crushed towards

the end of 1992. Nevertheless, there was a comprehensive failure to

understand the magnitude of the shift the induction of this new weapon

represented. At that time, the police and para-military forces were

armed, in the main, with World War II vintage .303 rifles, or the equally

obsolete bolt-action 7.62s. The Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF)

were marginally better off, with 175 Self Loading Rifles [SLRs] per

battalion. But even the SLR was no match for the sheer lethality of

the Kalashnikov. With counter-terrorist operations under my charge,

I pressed urgently for an upgradation of weaponry at this point. A large

number of Light Machine Guns [LMGs], acquired in the pre-Independence

era, were lying unused in their original packing in the armories of

various police stations all over the state. My demand that they be deployed

in the war against terrorism was met with shrieks of horror from the

school of thought – comprehending a majority among the central

and state leadership, administrators and senior police officers –

that adhered to the dogma that a ‘civil’ police force could

not be equipped with ‘military’ hardware, irrespective of

the circumstances. This curious dogma, in the prevailing situation,

translated into the proposition that the police must remain inept, inefficient

and ineffectual, simply because they were a ‘civil’ force.

It was only after strong personal insistence on my part, and against

the prevailing wiqdom of those in authority, that these weapons were

eventually brought out and mounted on key police stations, as well as

on escort vehicles of Station House Officers (SHOs) and other frontline

police officers.

Even worse than the failure to come

to terms with the magnitude and nature of the terrorist challenge was

the inchoate and utterly confused philosophy of the ‘political

solution’ that still dominated even the thinking of the police

leadership. The then DGP openly expressed the belief that the police

could not wipe out terrorism, but was only in a position to "control

it".16

In the meanwhile, ‘political solutions’

remained very much in vogue even after the dismissal of the Barnala

government in May 1987. Earlier, with the appointment of Siddharth Shankar

Ray as Governor, and of Julio Ribeiro as DGP in early April 1986, the

Centre had begun to publicly advocate the ‘hardline’ against

the terrorists. By May 1986, moreover, while the lame duck Barnala government

continued to preside over Punjab, law and order was directly overseen

by the Centre and a policy of competitive brinkmanship between various

parties at the Centre and the state ensued. The Centre continued with

the two-faced tactics of attempting to strike ‘deals’ with

various factions of the militants, even as it sought to mount pressure

on them through police action. The selective immunity consequently granted

to some terrorist groupings, the shifting strategies of ‘negotiation’

opened out with various known extremists, including, prominently, the

‘Jodhpur detenues’ – surviving associates and supporters

of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale who had been arrested during Operation

Bluestar – and a range of unprincipled political stratagem constantly

muddied the waters for the police.

Nevertheless, the police had begun to

commit itself for the first time in this long-drawn war – and the

conflict had certainly escalated to the level of warfare now. Between

May 1987 and April 1988 terrorists killed 1533 people in Punjab (a monthly

average of over 127), including 109 policemen. In turn, 364 terrorists

were also killed. But the vacillating and directionless policies of

the government, and the complete inability, indeed visible reluctance,

of the state to impose the rule of law – even in cases of the worst

acts of terrorism and where the perpetrators were apprehended by the

police – swelled the ranks of terrorist forces. Terrorism, which

had, in the past, largely been restricted to the districts of Amritsar

and Gurdaspur, now had another four districts – Hoshiarpur, Jalandhar,

Ludhiana and Faridkot – firmly in its clutches.

The government, however, persisted in

its opportunistic quest for just any kind of deal with the terrorists

to the very end. On March 4, 1988, 40 high profile prisoners –

the Jodhpur Detenues, including Jasbir Singh Rode – were released

as part of another compromise with terrorists. They simply walked into

the Golden Temple, where Rode was installed as the Jathedar (head

priest) of the Akal Takht [which was part of the deal]. Shortly thereafter,

the terrorists began to build up internal defences within the Temple

around the parikarma [which certainly was not].

The terrorist response to the Government’s

"goodwill gesture" was unequivocal. An unprecedented 288 people

– including 25 policemen – were killed in March and another

259 [including 25 policemen] in April.

With nothing left to trade, and 2866

lives [2207 civilians, 177 policemen, 482 terrorists] already sacrificed

at the altar of the false god of ‘political solutions between October

1985 and April 1988, the Centre decided that it was finally time to

enforce the laws of the land. This time, however, it was not the army

that was called in. Operation Black Thunder17

was executed squarely under the charge of the Punjab Police – backed

up by the elite anti-terrorist force, the National Security Guard [NSG]

and para-military forces. Its objective was identical to that of Operation

Bluestar – to clear the Golden Temple of the entrenched terrorist

forces. Unlike Bluestar, however, this was achieved in a clean, economical

and near-bloodless action, executed under the fullest glare of the media

– both national and international – within a week between

May 11 and May 18, 1988.

II

In the overall context of terrorism

in Punjab, Black Thunder was only a minor operation. Nevertheless, its

impact, in certain aspects, was critical. Though only a fraction of

the terrorists operating in the state were apprehended in the Temple,

it generated crucial structural transformations in the terrorist movement.

After Black Thunder, and the macabre exposures relating to the activities

of the extremists in the Temple, the movement for Khalistan could never

recover the facade of religiousity that had attended it in its early

years, and became increasingly and manifestly criminalised. Moreover,

the Gurudwara as sanctuary and safe-house for terrorists and

their leaders ceased to exist. It had been shown to be uniquely vulnerable

to a pattern of police action that would not agitate the devout, and

would inevitably force the renegade into police custody. The damage

done to the extremist cause was tremendous.

….the most significant…. was the loss of

the Golden Temple and the Gurudwaras as shield and sanction. Rape,

extortion and murder had been the business of the terrorists from

the very beginning of the movement; but in its initial phases, and

right up to the Black Thunder period, the top leadership was apparently

distanced from these activities, concentrated as they were in the

Golden Temple. Their depravity and vice in the hallowed place remained

unknown to the larger mass of Sikhs; and while lesser terrorists were

often seen to ‘stray from the path’, the highest motives

could still be ascribed to the militant leadership

Divested of the sanctuary of the Golden Temple and

the Gurudwaras, the leadership was forced to live life as fugitives

in the Punjab countryside; on the one hand, their own deeds exposed

them, and on the other, the deeds of their followers compromised them

even further, since they were now believed to be condoned, even encouraged,

by these leaders.18

I had assumed charge as Director General of Punjab

Police less than three weeks before Operation Black Thunder.19

After the successful execution of the Operation, I found, under my command,

a police force far from triumphant in this victory; deeply divided and

demoralised; ill-equipped, organisationally, materially and mentally,

to confront the larger challenge of eradicating terrorism from the entire

state. I had been serving in the state, but for a brief interregnum

(October 1985 – June 1986), since September 1984, in various capacities

that gave me state-wide jurisdiction, and I was more than familiar with

the difficulties encountered by the forces in Punjab. Specifically,

the problems that required immediate redress, and the steps taken to

tackle them – albeit gradually, and in a process that was often

frustrated by the lack of means and support from the political leadership

– included:

i. Inadequacy of the police stations to react

to terrorist violence on their own: The problem here involved manpower

and training, weapons, transport and communications. In most cases

of terrorist action, the local thana (police station) would

call for backup from headquarters or the para-military forces, and

no action would be taken till better equipped reinforcements arrived.

The inevitable delay rendered subsequent action more or less infructuous.

It was clearly necessary to minimize response time at the local level

by an enhancement of the thana’s capabilities. An across-the-board

upgradation of all police stations was, of course, financially unviable

and would have proven extremely wasteful. An exercise was carried

out to identify the police stations most affected by terrorist activity,

and to define the specific weaknesses of each of these. Many required

upgradation in terms of the officers in charge, and officers up to

the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police were placed in charge

of some sensitive thanas instead of Sub-Inspectors. Then came the

question of the necessary wherewithal to confront the terrorist. With

the right person in charge, additional manpower and improvement in

working conditions, communications equipment, and mobility were the

next priorities. But none of these would be of any use without the

necessary firepower.

Shortly before Black Thunder, a decision had already

been taken to equip the CRPF with SLRs and Automatic Loading Rifles

(ALRs), and also to increase the number of holdings of LMGs, and the

weapons were airlifted from Delhi to Punjab in April itself. The effect

of this upgradation of weaponry was immediately visible in the increased

capabilities of this force to repulse terrorist attacks, and to confront

the militants on a relatively equal footing. Unfortunately, the Punjab

Police was still equipped with the old .303s. To the ex-tent that

I conceived of this force as the core of the anti-terrorist campaign,

this was clearly unacceptable. In 1987, as stated before, unused LMGs

lying at various police stations in Punjab had been brought out and

mounted on sensitive police stations, as well as on the escort vehicles

of the station house officers of various sensitive thanas.

The LMG, however, clumsy and heavy as it was, was hardly a suitable

counter to the AK-47; nor could a couple of LMGs in each police station

secure the necessary counter to the thousands of AK-47s then in circulation

with the terrorists.

Even after Black Thunder, it remained difficult to

convince the Centre on the urgent necessity of providing the Punjab

Police with better weaponry and other equipment. Shortly after taking

over as DGP, I had communicated my views on three critical areas of

weakness in this regard. The first related to the core problem of

upgrading each police station in terms of the specific challenges

it was required to confront, with graded improvements in force strength,

transport, communications and weaponry. The second problem arose with

regard to the protection of individuals who required special security.

Such protection was generally poor, and there were numerous cases

where people who were being protected were shot down along with their

security guards. The third problem related to the force’s limited

capabilities to carry out night operations.

Unfortunately, while limited ad hoc sanctions

were made for improvements in communications and transport, resistance

to improvements in weaponry persisted. However, some limited improvements

were engineered in other critical parameters. A phased recruitment

of an additional 25,000 men in the Punjab Police, took the total strength

up to 60,000. Limited facilities for housing for police personnel

in protected enclaves were created. And some improvements at the thana

level were initiated through devices that were largely dependant on

man-management and on squeezing the most out of the limited resources

available to the police. The objective of the entire exercise of reorganisation

and upgradation of the thanas was to make each police station

capable of reacting immediately and independently to any act of terrorist

violence in its jurisdiction, and this was, in substantial measure,

secured in all sensitive police stations within the year 1988 itself.

ii. Extremely unfavorable ratio of operational

to static and non-productive force in manpower utilisation: It is

a matter of unending amazement to me that when I took over, between

40 to 50 per cent of the 35,000-strong Punjab Police force was, on

any single day, tied down to static and entirely unproductive duties.

The bulk of this number was immobilized at innumerable nakas

(barricades) all over the state, particularly in the cities and at

checkpoints on the highways. These barricades, at best, helped create

the illusion of security among the general public through massive

and visible police presence; at worst, they provided terrorists with

easy targets for drive-by shootings, or for a ‘weapon-snatching’

raid. Even in my early days in Punjab, I had taken up the matter with

some of my colleagues, but to convince officers of the Punjab Police

that this was a waste of human resources was difficult. Even those

who were convinced said that it was impossible to dismantle and disband

the pickets, since the political leadership thought this to be the

best strategy for policing.

Nothing could be more wasteful of the available manpower.

If ever a terrorist was apprehended or shot in an encounter at these

barricades, it was only the result of inordinate stupidity on his

part. Not only was the concept of police pickets and barricades passive

and manpower intensive, it was completely cost ineffective and irrelevant

in terms of the results it secured. In the months following Black

Thunder a large proportion of the personnel trapped at these nakas

was rapidly reallocated to create an operational force that comprised

as much as 85 per cent of the total personnel available.

The reallocation of forces and infrastructure also

involved a number of innovations, one of them being the formation

of mobile-cum-naka contingents – essentially mobile units

which would move in terrorist areas to ensure significant police presence.

Another innovation, and one that created an enormous psychological

impact on the ground, was the concept of ‘focal point patrolling’

under which all available vehicles in the district were brought to

a single location, creating an impression of massive force and a level

of saturation and mobility that did not, in fact, exist. Meetings

were called by senior officers, at the levels of IG and the DG, late

in the night, and in the most sensitive areas; since all subordinate

officers in the district were required to be present at such a meeting,

many vehicles and a substantial force would cluster at these locations.

The impact of a significant, even though transient, mobile police

presence in areas which had previously seen little police action,

and at night, was enormous.

iii. Infiltration of the police by elements sympathetic

to the terrorist cause, and deep communal divisions within and between

various police and para-military units: Communal propaganda that was

rife in the state for the past many years had certainly had an impact

on the forces. The PAP had a fairly large number of sympathisers in

its ranks, as did sections of the Punjab Police. On the other hand,

the para-military forces, drawn as they were from outside the state,

and with only a small proportion of Sikhs in their ranks, tended to

display a strong anti-Sikh bias. These attitudes inevitably spilled

over into the general public, and the common man reacted on a purely

communal basis to the personnel of each of the security forces operating

in their areas. The inherent contradictions of the prevailing situation

led to a lot of suspicion and mounting tension between the Punjab

Police and contingents of the various para-military forces in the

state. Indeed, in June 1986, Punjab Police personnel had clashed openly

with the CRPF at Amritsar, and, at one point, it appeared that there

would be an exchange of fire.

There were two distinct elements in this problem:

the one, of course, involved individuals who had been swayed by the

sustained fundamentalist propaganda of the past decade; the other

was structural, involving the interaction, or, more accurately, the

lack of interaction between various security forces operating in the

state.

It was essential to segregate compromised elements

within the Punjab Police and PAP from anti-terrorist work, and to

reduce their involvement in sensitive duties. It was equally essential

to do this discreetly, in order not to exacerbate communal sentiments.

A continuous exercise was carried out to identify and allocate personnel,

whose loyalties were suspect, to duties that would not undermine anti-terrorist

operations. Another priority was to ensure that officers selected

to lead in various theatres of the low intensity war in Punjab were

free of communal bias, and acutely conscious of the dangers posed

by fundamentalist thinking to the social fabric of the state.

The structural conflict between various wings of

the security forces appeared to be a more complex problem, but yielded

to solutions that were fairly simple. During my charge as IG PAP &

Operations at Amritsar I had already initiated, at the local level,

a process of correction. The core of the problem was that the various

forces were acting in isolation from, often in competition with, each

other. There was no sharing of information, and deep-rooted suspicion

of the actions of the other units. The Punjab Police, moreover, was

extremely resentful of the presence of the CRPF, and over the fact

that it was the local force that was being painted as villains by

the general public. There was also the natural tendency for each force

to regard its own work as the most important. It was clearly necessary

for each force to know what the other was doing, and was clear about

its own and the other’s role. This was simply not happening.

For instance, even where the CRPF caught a terrorist and handed him

over to the PP for interrogation, the intelligence acquired through

questioning would not be shared with the CPPF. To counter this trend,

joint interrogation teams were created, and a system established to

share available intelligence between all forces engaged in the anti-terrorist

campaign. In Amritsar, moreover, a process had been initiated dovetailing

the operations of the Punjab Police and the CRPF. Over a period of

time, the two forces began to fight as one, achieving levels of coordination

and cooperation under fire that made their earlier hostility and suspicion

seem irrational, even unreal. These strategies were now extended with

similar salutary effect across the state, and one of the most important

components of this exercise was the induction of selected officers

from outside the Punjab Police cadre to take care of Operations at

all levels.

At one time, the IG Operations was from the CRPF

and was also looking after the Punjab Police, permitting greater coordination

of forces and a systematic re-organisation on the ground.

iv. Near-complete absence of systematic intelligence

gathering and analysis: Successful counter-terrorist strategies are

based on accurate and detailed intelligence on terrorist networks

and activities. It was only towards the end of 1984 that the framework

of something resembling an effective counter-terrorist intelligence

apparatus was set up in Punjab. As stated earlier, even the routine

practice of record keeping in connection with terrorist crime was

entirely neglected by the Police administration in the early years

of the terrorist movement. The skeletal structure of an intelligence

operation was created under my charge as IG Operations after September

1984. Officers were ‘borrowed’ from the para-military forces

and from the PAP, records relating to terrorist crimes were prepared,

and investigations started. After Black Thunder, intelligence operations

went much deeper. It was no longer adequate to carry out an analysis

of terrorist movements at the state level; what was required was details

at the ground level in each police jurisdiction – down to the

level of each police station in the main affected areas. Police stations

were first identified and categorised as A, B and C grade, on the

basis of the intensity of terrorist activities. Then a village-wise

analysis was carried out. Certain villages were seen to be much more

active in their support to terrorism, not only in terms of recruitment

to terrorist ranks, but also by way of giving shelter and providing

information and material assistance to the terrorists. Gradually,

unique patterns emerged from the surface uniformity of terrorist operations

across the state. Gangs and their main operatives were identified,

their strength determined, their primary, secondary and tertiary spheres

of operation defined, their relationships of cooperation and hostility

with other gangs documented. Detailed information was also gathered

on sources and flows of weapon supplies, networks of safe-houses,

harbourers and sympathisers, cross-border routes of ingress and egress,

and a large body of corroborated data based on surveillance operations,

informers, interrogations and the progressive infiltration of many

of the terrorist gangs. By early 1989 itself, a fairly clear, accurate

and continuously updated picture was available on the jurisdiction,

membership, activities, strategies and networks of each of the major

gangs operating in the state. A continuous system of documentation

and analysis, and of dissemination of all received intelligence was

also introduced shortly after my assumption of command as DGP, and

periodic intelligence reports were received by all senior officers

of the police and para-military forces in the state.

v. Absence of a coherent strategy of response

to terrorist activity: Successes in counter-terrorist operations prior

to 1988 were largely the result of extraordinary initiatives on the

part of individual and exceptional police officers. By and large,

the terrorists controlled the field, striking at will, and often simply

walking away from the scene of the crime. Occasional pursuit and engagement

by courageous security men produced occasional successes. Nothing

approximating a systematic and independent response strategy at the

state level could be identified.

On the basis of the enormous intelligence exercise

initiated after Operation Black Thunder, however, it became possible

to carry out operations that were area, gang and terrorist specific.

The initiative progressively passed out of the hands of the terrorists,

and into those of the security forces. No doubt, the terrorists retained

the capacity to organise unpredictable and entirely random strikes

against soft targets; six years after the defeat of terrorism in Punjab,

they still possess this capacity. What they lacked, however, was the

impunity of operations that they commanded in the past. Each major

strike by the terrorists was followed up with major counter-terrorist

operations. The responsible group was targeted not only in the Punjab,

but in their safe-houses all over the country. The detailed information

available of their possible escape routes – including shelters

with the extended families of each terrorist, extended families of

terrorists who had been killed in the past, key sympathisers and harbourers

– made it possible to mount surveillance and concerted pursuit

operations that, even where they did not result in immediate arrest,

paralysed individual terrorists and prominent groups, reducing their

capacity to act in future.

vi. The failure of police leadership: The police

was being ‘led from behind’. Senior officers sought to run

operations by remote control, minimising their own exposure to risk.

The result was that, while deployment of forces was worked out on

paper, there was little or no direct assessment at the senior level

to see that orders were implemented on the ground, and no accountability

for failures to check terrorist activities within their jurisdiction.

As the same attitude percolated down to the field level, even the

most routine police and security functions began to be totally neglected.

The low casualty figures among security force personnel and terrorists

in the pre-1988 phase tended to reflect, at least in part, a tacit

arrangement between a majority among the police and the militants

that they would not cross paths.

Two parallel elements constituted the strategy to

create an active and accountable police leadership. One involved a

radical policy of postings and promotion through which sensitive areas

and critical anti-terrorist operations were headed by officers (often

very young officers) who were willing to confront danger and take

strong personal initiatives, and most of whom volunteered for these

high-risk assignments. A number of courageous officers from other

state cadres and from the para-military forces were also brought in

at crucial positions, while those whose motivation, loyalty or bravery

was suspect simply ‘opted out’ for softer postings, often

on deputation outside strife-torn Punjab.

But even the finest men cannot be asked to risk their

lives for a leader who will not lead from the front. Deeply conscious

of the honour and responsibility of commanding these men in a crucial

war for the nation’s unity and integrity, I made it my practice

to move constantly across the state, in areas worst affected by terrorism.

I had been touring the state continuously as IG Operations & (PAP)

(September 1985 – October 1986) and as ADG Law & Order (June

1987 – April 1988), directing and appraising anti-terrorist operations

– and the response had been most encouraging. These tours constituted

a pre-dominant part of my routine throughout the anti-terrorist campaigns

in the state, with, on the average, more than twenty-five days of

each month spent on the road, journeying again and again, deep into

the terrorist heartland.

The combined impact of these measures was enormous

and immediate. At one stage, there appeared to be a general consensus

– in the media, the public, the political leadership, and even

among police officers – that the police were demoralised, cowardly

and incompetent to face the challenge of terrorism. I soon found that

their ‘demoralisation’ was, in reality, only the absence of

clear directives from above; their ‘cowardice’ was only confusion

caused by conflicting commands, administrative sanctions and political

pressures; and their ‘ineptitude’ reflected only the absence

of a coherent strategy and a clear mandate for action.

People in Punjab’s villages spoke of a situation

where the police refused to move out of their barricaded police stations

after dark; the force’s will to fight terrorism, it appeared,

had been completely broken.

The appearances were deceptive. What had been lacking

was a clear mandate, and a freedom to carry on the battle without

crippling political interference. Throughout the era of the ascendancy

of terror, virtually every hard-core terrorist had a political patron;

police responses were distorted to such an extent that effective reaction

was precluded even in cases where policemen and their families had

been specifically targeted by the terrorists. But the will was far

from lacking.

Within five years, this very force was to spearhead

one of the most dramatic victories in the history of world terrorism.

The men who were said to have been cowering in their police stations

chased the terrorists deep into their own territory; and chased them

to their deaths.20

These five years, however, saw many reverses, a great

deal of perverse, pernicious political meddling, and enormous sacrifice

by nameless, faceless and now forgotten jawans and officers of

the forces that fought the terror.

In the days following Black Thunder, the terrorists

ravaged Punjab. 343 civilians were slaughtered in May alone. They included

30 migrant labourers working on the Sutlej-Yamuna canal in Ropar district;

another 45 migrant workers gunned down in Punjab and Himachal Pradesh;

and 20 killed in a bomb blast outside a temple in Amritsar. These reprisal

killings were a demonstration that Black Thunder had not decimated their

numbers in significant measure, nor undermined their capacity to strike

at will.

But the police made demonstrations of its own. The

swift redeployment and reorientation of forces bore immediate results,

and the civilian casualty rate fell rapidly. The first six months of

1988 had seen 1266 civilians killed, yielding a monthly average of 211

casualties; in the second half of 1988, 688 civilians were killed –

a high figure, but nevertheless a radical improvement – with the

monthly average down to 114. The terrorists, moreover, began paying

a heavy price. On July 12, ‘General’ Labh Singh, the head

of the Khalistan Commando Force (KCF), at that time one of the most

active terrorist gangs, died in an exchange of fire with the police.

Avtar Singh Brahma, another dreaded terrorist, was among the 68 terrorists

killed that month.

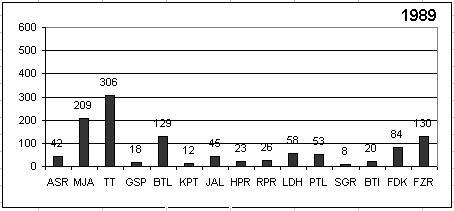

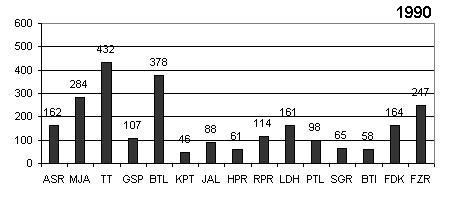

By January 1989, the terrorists had been pushed into

a thin strip along the border, with over 70 per cent of their strikes

restricted to just three of the twelve districts in Punjab – Gurdaspur,

Amritsar and Ferozepur. This proportion was to remain a constant throughout

1989 and well into 1990.

It was only natural to focus attention on this area.

In March 1989 a massive composite Special Operation – bringing

together the forces of the Punjab Police, the CRPF and the Border Security

Force (BSF) – was launched in the entire Mand area (a patch of

marshland primarily lying in the Amritsar and Ferozepur districts, but

flowing over into Kapurthala and Jalandhar as well), Ajnala, Jandiala,

Tarn Taran and Batala (along the river Beas). In a single month, 5280

villages and 8859 farm houses/behaks/deras were covered

in cordon-and-search combing operations. These special operations became

a regu- lar feature in the terrorist heartland, yielding a steady stream

of arrests and seizures of arms, ammunition and explosives, and mounting

pressures on the extremists that they found it progressively harder

to bear. The impact was compounded by highly focused intelligence-based

operations, as well as by the effective use of ‘spotters’

– captured terrorists who helped identify former associates. By

May 1989, the anti-terrorist drive had completely blunted the capabilities

of leading terrorist groups to strike at soft targets. The organisations

that that had been reduced to a negligible presence included the Khalistan

Liberation Organisation (KLO), the Bhindranwale Tiger Force of Khalistan

(BTFK) and the Babbar Khalsa, the last of which had perhaps the most

dedicated and resourceful, and the most dreaded, cadres.

Security operations, however, were not the only problem

the terrorists had. Black Thunder had already revealed that a majority

of recruits to the terrorist cause were found among common criminals.

Their exclusive motivation was crude profit, or the supplementary fruits

of the illegal power militancy conferred: access to women, to status

within the village, and, at the lower levels, to the minor perquisites

of the ‘trade’ – a motorcycle, dry fruits, liquor –

essential components of the idea of the ‘good life’ in rural

Punjab. Inevitably, the movement became highly criminalised and alienated

from even those segments of the general population that may, in the

past, have supported them. The top terrorist leadership – the two

‘Panthic Committees’, one that was eventually headed by Dr.

Sohan Singh [Panthic Committee (SS)], and the other dominated by Gurbachan

Singh Manochahal and Wassan Singh Zaffarwal [Panthic Committee (M)]

– was by now based entirely in Pakistan. Both groups were well

aware of these developments. Nevertehless, beyond making various ‘statements’

to cadres in India (as evidenced by ‘Press Notes’ and by correspondence

recovered from terrorists who were arrested or killed), and issuing

exaggerated threats of reprisal against those who were ‘defaming’

the movement through acts of extortion, rape and the murder of innocents,

they chose to do nothing. Their own power, and profits depended on these

criminal activities, and they were themselves too deeply compromised

for these statements to be taken as anything other than propaganda,

and they had simply no impact on the ground.

These were not the only signs of trouble in the rag-tag

armies of ‘Khalistan’. Violent turf wars broke out between

various gangs. There was, of course, already a deep and basic difference

at the highest level of leadership, divided as it was between two irreconcilable

‘Panthic Committees’ (a third ‘Panthic Committee’,

propped up by the Damdami Taksal, was also to emerge later, in September

1989). Pakistani handlers had made repeated attempts to mediate in order

to bring about some sort of rapprochement between these groupings, but

were entirely unsuccessful. The differences were hardly ‘ideological’;

indeed, neither group – or for that matter, no individual or grouping

in the movement for ‘Khalistan’ – was in a position to

project anything that could pass off as a coherent ideology. The disagreements

were largely a result of the bloody history of conflicts between the

various protégés of each Panthic Committee. Equally significant

was the distinctive constitution and strategy of these groups: The Panthic

Committee (SS) drew its cadres from a relatively educated urban/semi-urban

class, and executed operations primarily against marked targets (though

there were innumerable exceptions in which the general public was victim

to their violence). The Panthic Committee (M), on the other hand, drew

its support from rural Punjab and was dominated by the illiterate and

semi-literate; by and large, their ‘strategy’ was to create

as much chaos as was possible through completely indiscriminate killings.

With their emphasis on ‘soft targets’, groupings allied to

the Panthic Committee (M) were responsible for a preponderance of the

major terrorist actions in the 1988 and 1989 period, although its major

striking arm, the BTFK, had suffered enormous losses by mid-1989.

All this, however, was at a plane well above the murk

and depravity that marked the daily dealings of terrorist groups. Here,

the hard currencies of exchange were control over the narcotics trade

and gun-running; disputes did not arise out of ideologies, religious

principles, or tactical disagreements; personal ambition and greed were

the motives in ascendancy.

These factors helped the security forces tremendously,

as traditionally sympathetic sections of the population in Punjab grew

progressively disillusioned with the terrorists. The disillusionment

extended to the rank and file of the terrorists as well, many of whom

had visited Pakistan and seen the decadence and corruption of their

‘Chief Generals’, and others who saw the outright criminality

of their immediate leadership within Punjab.

The terror in the state had, till this point, been

absolute. Public cooperation with the police was meagre, and even in

the case of orchestrated public executions by small terrorist gangs,

there was virtually no protest or resistance from the people at large.

But all this began to change towards the middle of 1989. Since at least

some of the police weaponry had been upgraded after Black Thunder, there

were a substantial number of discarded .303 rifles available in police

armouries. A Village Defence Scheme (VDS), and a system of appointing

Special Police Officers (SPOs) was devised. The objective was to arm

volunteers in vulnerable villages to resist terrorist action at the

local level. The scheme was far from an immediate success. When I visited

a village in Jalandhar District after a number of killings there, I

called the village elders and suggested that the police could arm volunteers

so that they would not be as susceptible to sudden terrorist raids in

future. The response was outright refusal. The villagers were afraid

that the terrorists would selectively target the armed villagers, or

even the entire village, if any sign of resistance was shown. Nevertheless,

repeated visits over the following months and persistent efforts by

senior officers eventually bore fruit, and some villages responded positively.

Volunteers were trained in weapon-handling, and a number of gun license

holders were also involved; detailed tactical plans were drawn up for

the defence of each village; bunkers were built; initially, small police

contingents were also provided at night to buttress the local initiative.

SPOs, often army or police veterans, were placed in charge of each village

operation. A great deal of effort was expended to ensure that an effective

apparatus of self-protection was created, and that the scheme did not

degenerate into a cosmetic exercise in morale building. By April 1989

itself, 2350 weapons had been distributed in 451 villages, and the VDS

was to play a significant role to the very end of the war against terrorism.

There were other signs, small but nonetheless significant,

of the turning tide. On June 6, a bus was hijacked by terrorists near

village Talwandi Ghowan, PS Kathunangal, in the Majitha Police District,

Amritsar. The Hindu passengers were forced off the bus and were about

to be executed, when two Sikhs, Avtar Singh and Rajwant Singh, intervened

to save their lives. They were shot dead, and two other passengers were

seriously injured. The incident generated a great deal of revulsion

against the terrorists among Sikhs in Punjab. Then again, just a month

later (July 7), when a terrorist opened indiscriminate fire in the Tarn

Taran bazaar, he was over-powered and beaten to death by the shopkeepers

– an event virtually unimaginable even a few months earlier in

this heartland of the terrorist movement.

The combined impact of the pressure exerted by security

forces and the slow but definitive changes in the public response provoked

a panic among the leadership in Pakistan and their Pakistani handlers.

In March, Manochahal sent written instructions to his followers directing

them, among other things, to make hideouts in other states because of

the pressures in Punjab; he also instructed his top leaders to go underground

to avoid any further killings, as it was becoming increasingly difficult

to get new recruits. In April, another letter followed up with instructions

to create hideouts in Delhi and in far-away Bidar in Karnataka; a key

operative, Satnam Singh ‘Chinna’ was ordered to remain underground,

lest he was killed. Wassan Singh Zaffarwal similarly issued warnings

against the infiltration of government agents in his gangs and urged

his ‘Generals’ to step up falling recruitment. By May, militants

were being advised to use new routes to smuggle weapons across the border.

Jammu & Kashmir, Rajasthan and Gujarat were identified, and major

recoveries of weapons intended for Punjab were shortly to be made in

Rajasthan. By July, moreover, a number of hard-core and listed terrorists

had moved out of the Punjab and set up operations in the Terai region

of Uttar Pradesh, not as a measure to expand their areas of operation,

but to escape the increasing pressures in Punjab.

The pressure also forced a change in tactics and weaponry.

Militants in Punjab were advised to increasingly resort to the more

surreptitious device of the timed or remote controlled plastique explosive

device rather than the AK-47, which required them to be present at the

moment of execution. Explosive handling became an integral part of training

in the camps across the border after April, and some of the first significant

seizures of plastique explosives and sophisticated IEDS and timing devices

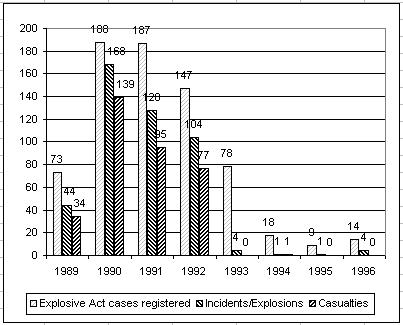

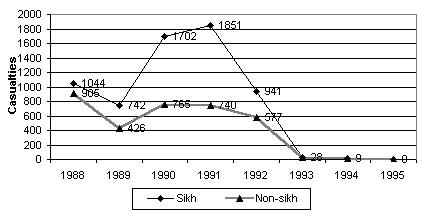

were made in May. (See Fig. 2).

The flood of weapons in the state also assumed new

and disturbing proportions. Till this point, weapons acquisition had

to be financed by the terrorists themselves through extortion and narcotics

smuggling. Suddenly, in July, messages were sent out that weapons "which

had accumulated in Pakistan for which no payment is to be made"

could be acquired by the simple expedient of sending "large numbers"

of terrorists across the border.

Since the beginning of the year, the terrorists had

mounted a sustained propaganda campaign to pressurise SPOs, Punjab Home

Guards [PHGs] and policemen from rural Punjab to resign their jobs on

pain of death, and to stop participating in the campaign against militancy

in the state. In March alone, some 60 Home Guards surrendered their

arms and left their jobs. A steady trickle of such desertions was to

continue in the months to follow. What was amazing, however, was that

despite a mounting campaign of targeted killings against them, the number

remained insignificant. This remained true even after September when

the campaign was extended to organised attacks on the members of the

families of policemen – despite mounting losses, the force gave

no quarter.

Fig 2: Trends in terrorist acts involving explosives in Punjab

The augmentation of the terrorist arsenal

led to a substantial escalation of terrorist activities. But civilian

casualties were held firmly down throughout 1989, even as the losses

inflicted on the terrorists, and by them on the police, mounted. Pakistan

was strenuously and openly directing the terrorist campaign at this

stage, to the extent that terrorist training camps were being organised

even within 75 metres of the international border (in the Ferozepur

sector). Border crossings re-mained a continuous and daily occurrence

along the 533 kilometre long international border Punjab shared with

Pakistan, and could never really be effectively checked, despite 122

kilometres of fencing that had been erected by August 1989.

However, exhaustion, the impact of a

continuous depletion in their ranks, declining trends in recruitment

and critical casualties among their leaders had taken their toll. Inspite

of every effort on the part of their Pakistani patrons, the morale of

all the terrorist groupings active in the state had taken a beating.

Tentative feelers were now being sent out. One by one, all the major

terrorist factions approached me for a face-saving solution. They wanted

to negotiate surrenders – and were willing to do so on their knees,

as long as they were not publicly humiliated, and as long as they could

escape the extreme penalties their actions over the past years would

attract under the normal course of justice.

Their various proposals were routed

by me to Delhi.

In the meanwhile, the campaign continued.

By the end of the third quarter of 1989, a fairly high rate of civilian,

terrorist and police casualties notwithstanding, the militants had been

pushed inexorably into a corner. Almost 76 per cent of all terrorist

incidents in 1989 were contained within four police districts along

the border (out of a total of 15 police districts in the state):21

Majitha, Tarn Taran, Batala and Ferozepur. More significantly, of the

fifteen police districts in the state, 10 were only marginally affected

by terrorist activities, with several months in the year passing without

a single killing there. At the end of the year, four of these districts

had an average civilian casualty rate of less than two a month;

in another six districts, casualties ranged between 2-5 a month. It

was only in the four ‘core districts’ that the average rate

ran into the double digits.

Even within these districts, the terrorists’

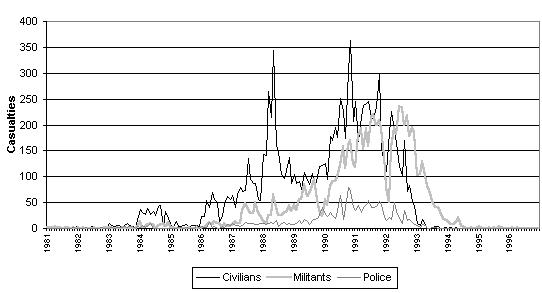

sway was not absolute. By the 4th quarter of 1989, just 13 police stations

accounted for nearly 65 per cent of all terrorist crime [and 64 per

cent of civilian casualties] in these critical districts. And out of

the 217 police stations in the entire state, nearly half the killings

had taken place within the jurisdiction of just these 13 police stations.22

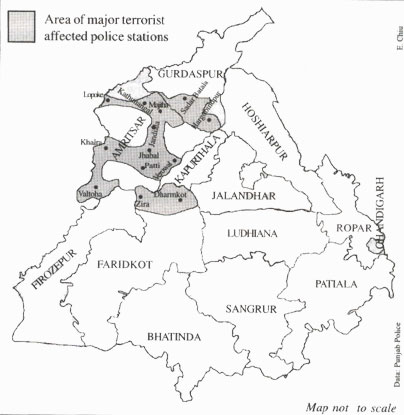

Fig 3: Major terrorist Affected Areas in the 4th Quarter of 1989

I was then, and still remain, absolutely

convinced that terrorism, at this juncture, could have been wiped

out in the state of Punjab within another six months of sustained

campaigning.

III

Politics, however, was destined to

intervene once again. At a time when the militants were imploring

the government for a general amnesty with greater passion and urgency

than had ever attended their demands for Khalistan, the Centre refused

to respond. A general election was now imminent, and a deeply discredited

regime, swamped under charges of corruption and nepotism, sought to

play on popular insecurities. Terrorism became the critical issue

of its election campaign – the Congress-I alone, it proclaimed,

could defend India against the menace of militancy. At this juncture

it appears that the party leadership believed it could profit by allowing

the sore to fester a little longer. Once it returned to power, of

course, the Punjab problem would be sorted out soon enough.

The moment passed. Soon it became

amply evident that the Congress-I would not return to power at the

Centre. The offers of conciliation petered out as the militants decided

to bide their time.

The announcement of elections itself

had a destabilising impact in Punjab. Unmindful of the critical juncture

at which the anti-terrorist campaign stood, and the inherently unstable

character of the equation that had been established, the Rajiv Gandhi

government decided to press ahead for elections in the parliamentary

constituencies in this state as well.

The All India Sikh Students Federation

had, by now, decided to complement its underground activities with

an over-ground role. It combined with Simranjit Singh Mann’s

pro-militant United Akali Dal [UAD], and the extremist front organisations

swept the poll, with 10 of the 13 seats going to candidates backed

by the alliance. Before demitting office, Rajiv Gandhi ordered the

release of Simranjit Singh Mann, and of Harminder Singh Sandhu and

Atindar Pal Singh of the AISSF. All cases against them were arbitrarily

dropped to give ex-pression to what was then, perhaps, a proposition

unique to Indian justice administration, that a man elected to Parliament

may not be tried for any crime that he may have committed.

The war against terror, as with all

wars, is fought as much in the minds of men as it is on the field

of battle. The V P Singh government that took oath of office on December

6, 1989, brought with it preconceptions, attitudes and a pervasive

confusion that surrendered the initiative to the terrorists even before

they engaged.

The defining incident with regard

to this Government’s policy on terrorism occurred within the

first week of its installation. The daughter of the newly appointed

Home Minister was kidnapped in Kashmir (on December 11, 1989) by what

was then an incipient terrorist movement in that state. The government’s

response was absolute capitulation – and, within days, Kashmir

simply exploded into a full-blown insurgency that is still to be brought

under contrml.

The message to extremists all over

the country was abundantly clear: this government had neither the

will nor the understanding to define and implement a cogent and resolute

policy against terrorist violence.

V P Singh’s policy orientation

to terrorism in Punjab was, in all its simplicity, comprehended by

the expression frequently used by him: ‘healing hearts’

he believed, was all that was needed. Two of his most prominent advisors,

ethnic Punjabis, but completely alienated from the peculiar politics

of the state and inconceivably ignorant of the nature and magnitude

of the terrorist threat, were quite convinced – and apparently

succeeded in convincing their Prime Minister – that terrorism

had long been kept on an artificial respirator by the Rajiv Gandhi

regime. With the election of the Janata Dal government, it would simply

‘wither away’. All that was required was a little symbolism,

a few sympathetic, sentimental gestures, and the violence, the terror,

would melt away.

The first gesture came a day after

the swearing in, when V P Singh visited the Golden Temple. This was

followed by a public meeting at Ludhiana on January 11. No concrete

strategy, approach or plan for the resolution of the state’s